By Robert Allison

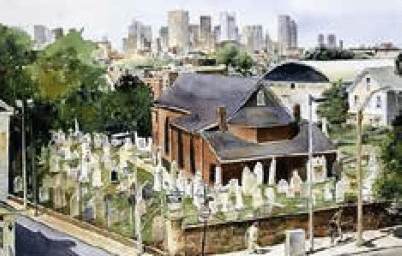

Like Castle Island and Dorchester Heights, St. Augustine Chapel and Cemetery is an historic site with national significance which has been entrusted to South Boston. St. Augustine’s Cemetery is New England’s oldest Catholic burying ground. The Chapel, which opened on July 4, 1819, is the oldest Catholic church in Massachusetts. St. Augustine Chapel and the Cemetery have witnessed two centuries of history, and we now have the opportunity to ensure they continue to inspire generations to come.

Bishop Jean Cheverus and Father Francis Antony Matignon arrived in Boston in the 1790s, refugees from France’s revolutionary turmoil. Both were scholars and thinkers—Matignon, with a doctorate in theology from the Sorbonne, had been Cheverus’s teacher. But they earned the respect and friendship of Bostonians through their sincerity and compassion. Cheverus personally delivered firewood (and evencut it himself) to the destitute and risked his own health to tend the sick and dying during a devastating Yellow Fever outbreak and spent months each year as a missionary to Maine’s Passamaquoddy Indians. When Cheverus and Matignon set out to build a permanent church—the Church of the Holy Cross on Franklin Street—President John Adams was the first benefactor, and architect Charles Bulfinch provided plans at no charge. The Church of the Holy Cross had to be large enough both for Boston’s two hundred or so Catholics, but also for the many Protestants eager to hear the eloquent Cheverus preach.

More than a thousand Bostonians followed Matignon’s casket from the Cathedral to the Granary in September 1818, on a day when it was said all Boston was Catholic. Two months later, on December 21, more than a thousand mourners again followed Matignon’s casket from the Granary, down along the Common to Washington Street, and across the Fourth Street Bridge to South Boston. Father Matignon was again laid to rest, in this parcel which Bishop Cheverus had bought for $680 to be a Catholic cemetery. Cheverus left a blank space on Father Matignon’s stone, anticipating that one day he would be laid to rest with his friend.

Father Philip Lariscy, an Irish Augustinian, raised $1700 to build the chapel, which was dedicated on July 4, 1819.In honor of Lariscy, Bishop Cheverus named the twenty by thirty-foot chapel for St. Augustine. Its Gothic-style windows evoked the ancient churches of his and Matignon’s native France, and on Sundays the Bishop would retreat here, to this quiet spot shaded by elms below the slope of Mount Washington.

But Cheverus would not stay in Boston. He was called back to France, where he became the Cardinal in Bordeaux. More Catholics arrived in Boston, and Cheverus’s successor, Bishop Benedict Fenwick, expanded the Cemetery to F Street, and expanded the Chapel in the early 1830s. Though it was first a mortuary chapel, as South Boston’s Catholic population expanded, St. Augustine’s became a parish church. With the opening of the Church of St. Peter and Paul in the 1840s it fell again into disuse except for funerals, then in the 1870s again became a parish church, with Father Denis O’Callaghan holding services here while also building the larger St. Augustine’s Church further down Dorchester Street.

More than a thousand people are buried in St. Augustine’s. Along with Father Matignon are some of the new nation’s early clergy and religious: Patrick Byrne, the first priest Bishop Cheverus ordained; Sister Saint Henry, an Ursuline nun who died shortly after the burning of the Convent in Charlestown; James McGuire, pastor of Portland, Maine’s first Catholic church; Reverend Stanislaus Buteux, born in France, the first priest in the territory of Terre Haute, Indiana; Angelo Contino, born in De Busca, Italy; and Rev. Alexander Sherwood Healy, pastor at St. James Church in the South End. Reverend Healy died at the age of 39 in 1875, a year after his brother Patrick, a Jesuit with a Ph.D. from Paris, became the president of Georgetown, and the same year his brother James Augustine Healy was consecrated the Bishop of Portland. The Healy brothers were born in Georgia, where their father, an Irish immigrant, was a cotton planter, and their mother Eliza had been enslaved.

The Healys sent their sons and daughters north for an education—four sons became priests, and three daughters became nuns. Bishop Healy provided St. Patrick’s Church in Damariscotta, Maine, with a set of French lithographs depicting the Stations of the Cross—are the French Stations of the Cross in St. Augustine Chapel a related set? In addition to the clergy, the Cemetery is the final resting place of the parents of Bishop John Bernard Fitzpatrick, the Diocese of Boston’s third prelate, and the parents of his successor Archbishop John Williams. Also, here are Patrick Donahoe, publisher, and editor of the Pilot; Christopher Connor, the first Catholic elected to Boston’s board of alderman; Barney McGinniskin, the first Irish police officer in the United States; the sister-in-law of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton, who corresponded with Cheverus when she questioned her new faith; at least six men who served in the Civil War, and a thousand other men, women, and children. Every Irish county but one is represented on the stones of St. Augustine’s.

Despite its significance, St. Augustine Chapel and Cemetery has been neglected over its long history. Anniversaries have been occasions to restore and repair it. For the 75th anniversary in the 1890s, Archbishop Williams presided at the dedication of the stone wall blocking it off from the surrounding streets. For the centennial in 1918, Cardinal O’Connell presided at a Mass. On the 125th anniversary in 1944, Bishop Richard Cushing officiated in a day-long celebration which included a mass as well as a parade, speeches by Governor Saltonstall, Mayor Tobin, and Congressman McCormack, the restoration of 170 headstones and the marking of veterans’ graves. For the 175th, it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places and brick paths were laid through the Cemetery.

For the bicentennial, a new roof, synthetic material that looks like the original slate, but is more durable and lighter, has been installed. The iron fencing is being replaced, to make the surrounding more welcoming (but still secure). Volunteers have been cleaning the graves. Funds from the Community Preservation Act have been critical to the work, as has support from volunteers. On September 15, close to the anniversary of Father Matignon’s passing, Cardinal Sean O’Malley will say Mass in St. Augustine Chapel. This is an opportunity to reflect on the community of faith which Cheverus and Matignon shepherded in those troubled early years, on the many men, women, and children whom the faith sustained, and on how we can secure their historical memory for those who will follow them and us.